|

STORY / TEKS:-

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com

Pop-art pioneer Robert Rauschenberg dies

By Mitch Stacy

The Associated Press

TAMPA, Fla. — Robert Rauschenberg, whose use of odd and everyday articles earned him a reputation as a pioneer in

pop art but whose talents spanned the worlds of painting, sculpture and dance, has died, his gallery representative said Tuesday.

He was 82. Rauschenberg died Monday, said Jennifer Joy, his representative at PaceWildenstein gallery in New York.

Rauschenberg, who first gained fame in the 1950s, didn't mine popular culture wholesale as Andy Warhol did with Campbell's

soup cans and Roy Lichtenstein did with comic books.

Instead,

his "combines," incongruous combinations of three-dimensional objects and paint, shared pop's blurring of art and objects

from modern life.

He also responded to his pop colleagues

and began incorporating up-to-the-minute photographed images in his works in the 1960s, including, memorably, pictures of

John F. Kennedy.

Among Rauschenberg's most famous works was "Bed,"

created after he woke up in the mood to paint but had no money for a canvas. His solution was to take the quilt off his bed

and use paint, toothpaste and fingernail polish.

Not to be limited

by paint, Rauschenberg was a sculptor and choreographer and even won a 1984 Grammy Award for best album package for the Talking

Heads album "Speaking in Tongues."

"I'm curious," he said in 1997

in one of the few interviews he granted in later years. "It's very rewarding. I'm still discovering things every day."

Rauschenberg's more than 50 years in art produced a varied and prolific collection that that filled both Manhattan locations

of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum during a 1998 retrospective.

Time magazine art critic Robert Hughes, in his book "American Visions," called Rauschenberg "a protean genius who showed America

that all of life could be open to art. ... Rauschenberg didn't give a fig for consistency, or curating his reputation; his

taste was always facile, omnivorous, and hit-or-miss, yet he had a bigness of soul and a richness of temperament that recalled

Walt Whitman."

Rauschenberg split his time between New York and

Captiva Island in Florida, where he kept a house stocked with his own art and those of his friends.

"I like things that are almost souvenirs of a creation, as opposed to being an artwork," he said in a 1997 Harper's Bazaar

interview, "because the process is more interesting than completing the stuff."

He studied painting at the Kansas City Art Institute in 1947. He later took his studies to Black Mountain College in North

Carolina, where he studied under master Josef Albers, and alongside contemporary artists such as choreographer Merce Cunningham

and musician John Cage. He also studied at the Art Students League in New York City.

Rauschenberg first paintings in the early 1950s comprised a series of all-white and all-black surfaces under laid with wrinkled

newspaper. In later works he began making art from what others would consider junk — old soda bottles, traffic barricades,

and stuffed birds and calling them "combine" paintings.

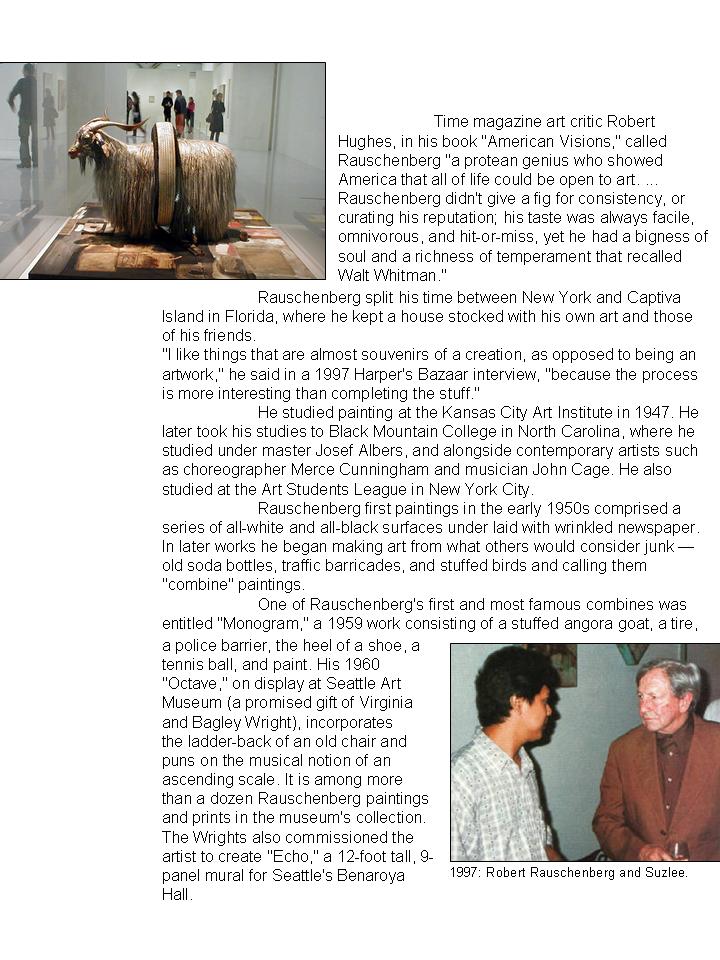

One of Rauschenberg's

first and most famous combines was entitled "Monogram," a 1959 work consisting of a stuffed angora goat, a tire, a police

barrier, the heel of a shoe, a tennis ball, and paint. His 1960 "Octave," on display at Seattle Art Museum (a promised gift

of Virginia and Bagley Wright), incorporates the ladder-back of an old chair and puns on the musical notion of an ascending

scale. It is among more than a dozen Rauschenberg paintings and prints in the museum's collection. The Wrights also commissioned

the artist to create "Echo," a 12-foot tall, 9-panel mural for Seattle's Benaroya Hall.

"I think he's got to be one of the top 4 or 5 artists after World War II," said SAM contemporary art curator Michael Darling.

"He is so important and was doing so many things before other people were doing them. I continually grow in my admiration

for him as time goes on."

Rauschenberg's son Christopher, a photographer,

graduated from Evergreen State College in 1973 and now lives in Portland, Ore.

Early life

By the mid-1950s, Rauschenberg was also designing sets and costumes

for dance companies, and window displays for Tiffany and Bonwit Teller.

He met Jasper Johns in 1954. He and the younger artist, both destined to become world famous, became lovers and influenced

each other's work. According to the book "Lives of the Great 20th Century Artists," Rauschenberg told biographer Calvin Tomkins

that "Jasper and I literally traded ideas. He would say, 'I've got a terrific idea for you,' and then I'd have to find one

for him."

Born Milton Rauschenberg in 1925 in Port Arthur, Texas,

and raised a Christian fundamentalist, Rauschenberg wanted to be a minister but gave it up because his church banned dancing.

"I was considered slow," he once said "While my classmates were reading their textbooks, I drew in the margins."

He was

drafted into the U.S. Navy during World War II and knew little about art until a chance visit to an art museum where he saw

his first painting at age 18. He drew portraits of his fellow sailors for them to send home.

When his time in the service was up, Rauschenberg used the GI bill to pay his tuition at art school. He changed his name to

Robert because it sounded more artistic.

In recent years he founded

the organization Change Inc., which helps struggling artists pay medical bills.

"I don't ever want to go," he told Harper's when asked about dying. "I don't have a sense of great reality about the next

world; my feet are too ugly to wear those golden slippers. But I'm working on my fear of it. And my fear is that something

interesting will happen, and I'll miss it."

Seattle Times art critic

Sheila Farr contributed to this report.

Copyright © 2008 The Seattle Times Company

|